I was confronted by a recent headline that read:

ESOL outdated: English for speakers of other languages guilty of othering

ESOL stands for English for Speakers of Other Languages. In New Zealand and other English-speaking countries (eg, Australia, US), the term is used to differentiate the intended audience from mainstream English language instruction.

The article claims that “there is something Anglo-centric and othering about the term”. There’s an argument to be made that someone not born into an English speaking environment and who receives English language training is orienting themselves to an ‘Anglo’ worldview, eg, that English is important for them to want to learn it, that the world they live in or wish to live in operates on an English-speaking basis and all its norms and assumptions. The term is also Anglo-centric in that it is those who provide that type of English language instruction are dominated by the Anglo centres of the world (ie., US, Canada, UK, Australia, New Zealand).

I recognise that Anglo-centricity can give rise to othering, but it is also important to distinguish between the issue of Anglo-centricity – that is, how the English language and associated culture is the dominant and unquestioned way of life, and the issue of othering – marking someone or some group as different with intended or unintended negative connotations.

We can use any number of labels to identify those who are learning the English language, and labels in the English learning and teaching context help to differentiate pedagogical approaches. Whether the label or term becomes ‘othering’ will depend on the context in which it is used.

For the learner, ESOL might be a strange term for them since it’s a given that they speak other languages. Why not simply call it an English language class? Or better yet, describe what they can do with the English, eg, Conversational English, English for Work, Everyday English. And this is probably what happens with naming English classes. So while ESOL is used to refer to the type of English language instruction, learners don’t necessarily use the term to describe their own learning. So whether the term ESOL is ‘othering’ for the learner may be moot as they simply consider themselves English language learners.

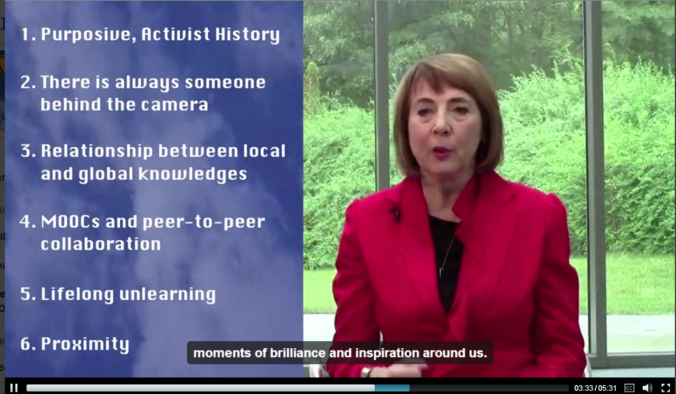

Then what about others who use the term, like teachers of ESOL? The teaching of ESOL (or TESOL) as a type or approach of English language instruction will vary among teachers, but we can look to TESOL International Association for a core set of 6 principles for the exemplary teaching of English learners:

- Know Your Learners

- Create Conditions for Language Learning

- Design High-Quality Lessons for Language Development

- Adapt Lesson Delivery as Needed

- Monitor and Assess Student Language Development

- Engage and Collaborate within a Community of Practice

These principles are intended to:

- respect, affirm, and promote students’ home languages and cultural knowledge and experiences as resources

- celebrate multilingualism and diversity

- support policies that promote individual language rights and multicultural education

- guide students to be global citizens

So if we hold the teachers of English to speakers of other languages to the principles and intentions of affirming the learners’ home languages and cultures, the term ESOL is far from ‘othering’: it is inclusive, respectful and aspirational.

And to go back to the issue of Anglo-centricity, the underlying ethos of the terms ESOL and TESOL would appear to challenge the status quo of Anglo-centricity in a way that aims to be beneficial for both English language learners and the wider community.

So why this accusation of ‘ESOL’ being guilty of ‘othering’? The ESOL terminology not only serves to make clear the audience of English language instruction, but also aims to affirm learners’ heritage and their linguistic and cultural resources.

It’s encouraging to know that there are advocates for inclusivity and those who call out discriminatory language. But has the word ‘other’ in ESOL tripped people up? There’s nothing othering about the term nor its intended use. And it’s concerning if we start reading ‘othering’ into a term that means no harm.

Sure, re-name course titles and qualifications to signal a wider audience of English language learners. But don’t erase a term or label when there’s a useful function for differentiation, and more importantly, when there’s a specific intention of making learners the centre in language training.

If we want to deal with ‘othering’, let’s look beyond the single word or label. Better yet, let’s welcome the ‘other’ relative to ourselves. If we recognise that those who are learning English speak ‘other’ languages, how about we start to be curious about their languages, and unpack what this ‘other’ means to us, and start to unravel a multitude of languages we can recognise, learn and embrace?

And if you’re ready, you’re in luck. New Zealand Chinese Language Week is coming up and runs from 25 September to 1 October. As a speaker of English, Mandarin and some Hokkien, I’m delighted to share ‘other’ languages with you, and I’m curious about ‘other’ languages different communities around me speak.

Ko taku reo, taku ohooho, ko taku reo taku mapihi mauria.

My language is my awakening, my language is the window to my soul.