We’re constantly bombarded by ‘get-rich-quick’ schemes – 5-day weight loss program, 3 days to a better you, be an overnight millionaire in a never-to-be-repeated 1-day course. I’ll admit I’ve been seduced by these promises of a sure-fire way to get what you want, only to find shortcuts end up as short circuits. There’s a power surge and the lights go off – and my enthusiasm goes *poof*

To be clear, if you’re attracted to a piece of advice and a pathway to success, by all means check it out and see if it makes sense and works for you. My own experience is that any change I want to see in myself or my circumstances depends on three things: motivation, habits, and accountability. For example, I had a repeated sprain in my arm for the past 6 months and this was related to a mixture of stress, body posture and working from home too much. I was motivated to fix this problem, so I signed up for a weekly Qigong class, and I had a physiotherapist friend check in to see if I was putting stretching and breathing lessons into practice. 4 weeks into the classes, I’m no Zen master but I certainly feel lighter and my arm looks to be sprain free – touch wood!

My experience with fixing my sprained arm parallels another real life issue – finding out about job opportunities. In this very tough employment environment, networking and uncovering the hidden job market becomes so important that I find myself prioritising this over refreshing the Seek job listings. Motivation – big fat check. As for habits – I needed to get myself out of this abyss of gloom and out into the real world of people and conversations.

Networking and Weak Ties

Networking is not just a buzzword for me. Networking is a concept built on the idea that networks are many connections (of people) linked on the basis of family, friendship, personal interests, employment, industry, business, and so on and so forth. My own PhD research utilised the principles of social networks and relationships to understand how first year international students sought out help for their assignments.

One of the most important ideas about networking pioneered by Stanford professor Mark G. Granovetter is that weak ties (eg, acquaintances, former colleagues) give you relatively more useful information than strong ties (eg, family, friends). Family and friends in your existing social circle hold information that you are already privy to, while acquaintances, former schoolmates and colleagues whom you don’t interact with on a regular basis are more likely to have information about jobs or leads that are unknown to you. (I highly recommend reading Granovetter’s seminal article “The Strength of Weak Ties”.)

Planned Happenstance

While the idea and evidence of the strength of weak ties is compelling, the actual reaching out to weak ties is another thing altogether. Here is where Planned Happenstance, a theory developed by another Stanford luminary the late John D. Krumboltz, comes into play (Mitchell, Levin, & Krumboltz, 1999; Krumboltz, 2009). Planned happenstance is about creating and transforming unplanned events into opportunities for learning and action. Yes, the term ‘planned happenstance’ is a deliberate oxymoron: ‘planned’ suggests being deliberate, while ‘happenstance’ appears to be fate or pure luck. Planned happenstance is not about relying on a lucky break or a knock on the door (and then never have it happen). Rather, it is about taking action to generate and find opportunities.

To illustrate, imagine that all day long you keep thinking you’re going to strike it rich by winning the lottery. You pray to the gods that you’ll be given lucky numbers. But nothing happens – because you haven’t even bought a ticket. So imagine you’re hoping that someone will shoulder tap you for your dream job. You pray to the gods you’ll be given the job you’ve been waiting for all your life. But nothing happens – because you haven’t left the house in the past 2 weeks.

In their book “Luck is No Accident”, Krumboltz and Levin sum it up like this:

“You have control over your own actions and how you think about the events that impact on your life. None of us can control the outcomes, but your actions can increase the probability that desired outcomes will occur. There are no guarantees in life. The only guarantee in life is that doing nothing will get you nowhere.” (Krumboltz & Levin, 2010, p. 9)

So what next? What are the habits we can cultivate to get us into action?

Make Your Own Luck

Prepare for action – Take small steps, do something different, say”yes,” and then work out how you’re going to do it. Your mind can limit what you believe you can do. So train your mind to say yes, rather than no, and develop a bias for action. One way that works for me is to consciously sign up for a networking event or say yes to a social function. It puts something in my calendar and gives me a runway of a few weeks to think through how I might prepare myself. One recent example is how I said yes to be a discussant for an international education research forum. There was one empty slot taking place in about a month, and when I was asked if I wanted to lead the session I said yes – not having a clearly defined topic in mind, or worrying too much about what others might think of me. I work best with deadlines, and as the date in June drew closer, I got my mind attuned to my research and developing key messages for the audience.

Overcome barriers to action – Realise that if your action fails, you are no worse off than if

you did nothing. Don’t forget to celebrate your small successes. Participate in confidence-building exercises, such as accepting compliments gracefully. I’ve sat in front of the laptop for many days on end, doom-scrolling through the jobs that either didn’t interest me or were jobs that I could certainly do – and so could hundreds more. I did have a job interview a few weeks ago which I thought went very well, but in the end they found someone else – and there were many great candidates to choose from. I was disappointed but nonetheless encouraged by the hiring manager’s feedback that they enjoyed interviewing me (which tells me it wasn’t just me thinking I had a great interview). I accepted that feedback and considered it a successful outcome – that I prepared well and the interview panel were impressed with my answers. This helps me be confident for the next interview opportunity.

Take action! Network, socialise and build relationships. At the next networking event or social function, aim to speak to three new people. Share your interests and experiences with people that you meet. You may find leads in the least expected spaces. I recently attended a networking session in Wellington organised by Yes for Success (formerly known as Dress for Success). I spoke to a few people and found out about contract marking which I’ve never considered. I also found out that Yes for Success had just launched a mentoring programme. I subsequently emailed them about it and spoke with the coordinator. I’m now looking forward to a possible mentor match who could also be an accountability partner in my foray into a new career reality.

Choose Your Own Adventure

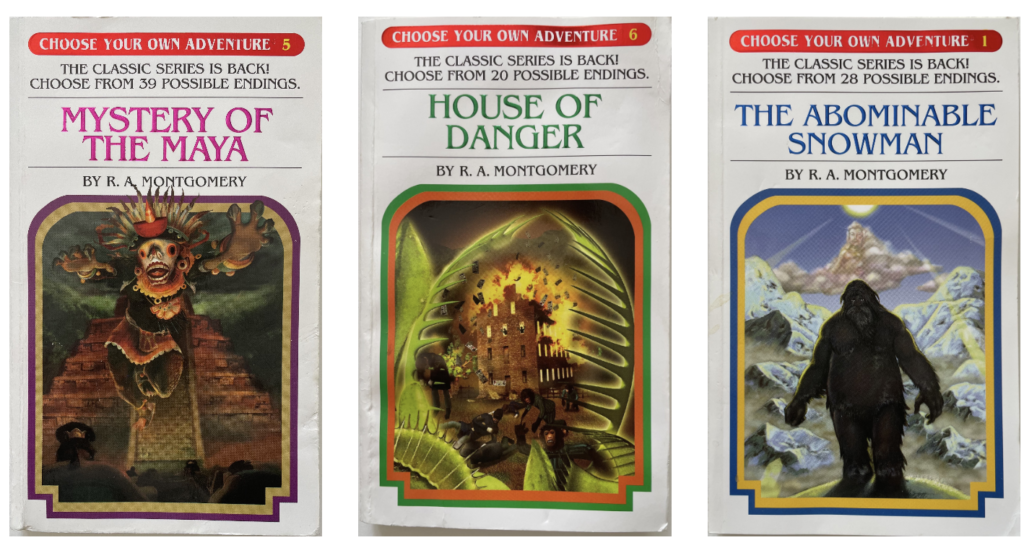

When I was growing up in the 80s, I read Choose Your Own Adventure books. I was hooked from the beginning with some trouble brewing head, a catastrophe to prevent, or a monster to fight. I loved it because I could play the hero and explore the different decision options, and hoped my choices didn’t lead to an ending that got me trapped under the quicksand forever.

Career transitions are becoming my new Choose Your Own Adventure books. With nothing much to lose, I’m been experimenting with different ideas and career options. Unlike the books I read, I can’t go back to page 75 and try a different course of action, but I can create many more pages of possibilities and endings. Plus I know I won’t get trapped under the quicksand forever. But not doing anything will.

References

Granovetter, M. S. (1973). The Strength of Weak Ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78(6), 1360–1380. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2776392

Krumboltz, J. D. (2009). The Happenstance Learning Theory. Journal of Career Assessment, 17(2), 135-154. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072708328861

Krumboltz, J. D., & Levin, A. S. (2010). Luck is no accident: Making the most of happenstance in your life and career (2nd ed.). Atascadero, CA: Impact Publishers.

Mitchell, K. E., Levin, A. S., & Krumboltz, J. D. (1999). Planned happenstance: Constructing unexpected career opportunities. Journal of Counseling & Development, 77(2), 115–124. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.1999.tb02431.x